Today was our first mediated field experience with the high school students in the TPP study. We met with them in the morning in their teacher’s classroom, and briefly reviewed how to begin the quick image routine (which they would be doing with 2nd graders). TPP students worked in pairs and took turns rehearsing their launches of the routine. There was some nervous laughter interspersed with encouragement from the ‘listening’ partner. After a few minutes of this turn-taking mini-rehearsal, I (Charlotte) invited a few students to do a public rehearsal of their launch, and then did her own rehearsal. We discussed a few key reminders (the central instructions are for students to figure out how many they see and how they see them; ask students to turn and talk with a partner before sharing out; remember to change colors of markers as you annotate different students’ ways of coming to the total number). Then we loaded up our things and walked next door to the elementary school.

Once inside, we were welcomed into Ms. D’s 2nd grade classroom where students were finishing their breakfasts, using the restroom and washing hands, or reading a book –Ms. D. calls this “doing what you need to get done before starting the day.”

We introduced ourselves to the class during morning meeting, in which the students, the TPP students, and the research team members introduced ourselves in a ‘greeting circle,’ followed by the pledge of allegiance and a choral calling of sight word sounds. I noticed as I watched the students participate in these routines that they seemed ready, alert, confident, and comfortable with the expectations their teacher had for them.

Next, I introduced the students to what we would be doing by relating the learning of teaching to learning to ride a bike: that the initial experiences can be wobbly, a little scary (“exciting scary, not dangerous scary”) and that as learners they could support their TPP teachers by being patient, forgiving, kind, generous with their thinking, and encouraging. We then broke into three groups.

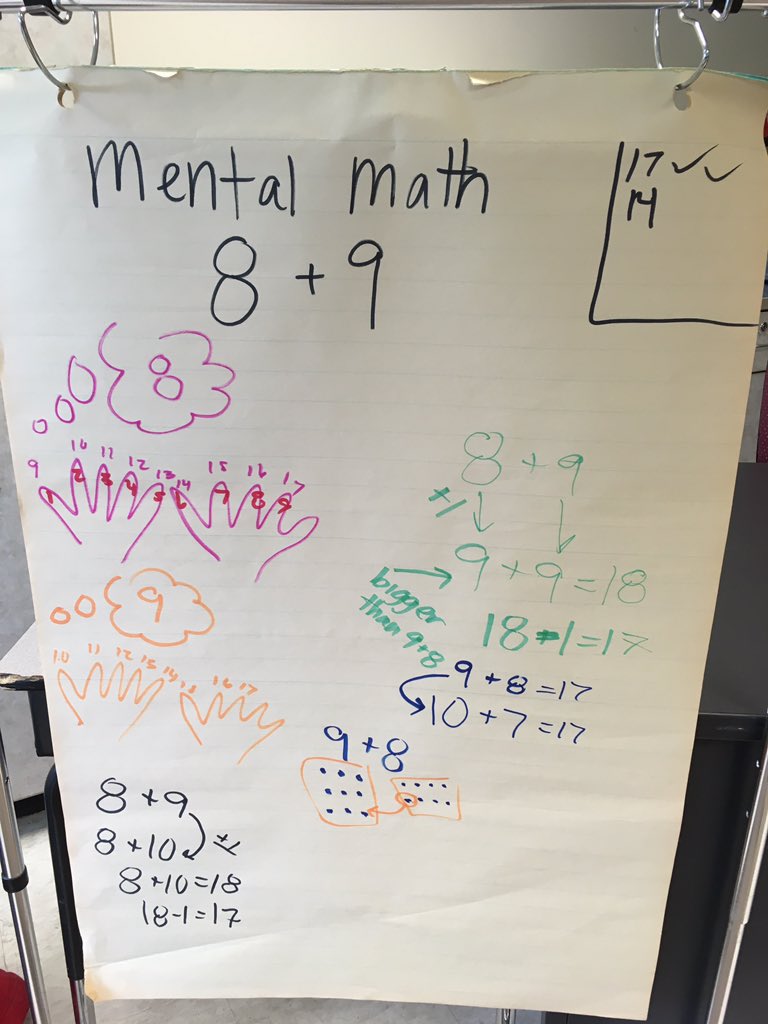

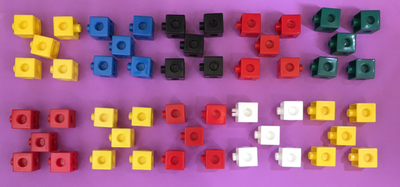

The TPP teachers led their quick image routines with cool confidence. I was able to observe Ben and Amira, who facilitated their discussion with a group of 5 students in a small alcove by the cubbies near the entrance of the room. Ben reviewed the instructions, as we’d rehearsed, and gave students a lot of wait time after initially ‘flashing’ the image. He encouraged the students to show a thumbs up when they had an idea to share. Once everyone was ready to share, he collected answers from the students, and then shifted to asking them how they had counted. “By 5s!” was a common response, but not all saw the image this way – one student had counted by 3s, and another had grouped the 5s into rows like a ten-frame.

Ben waited, listened, and did his best (with reminders from Amira) to show students’ ideas by circling and grouping the cubes with different colored dry-erase markers. Ben moved the discussion to means of representing ideas using numerals – using number sentences or skip counting notation to show student thinking.

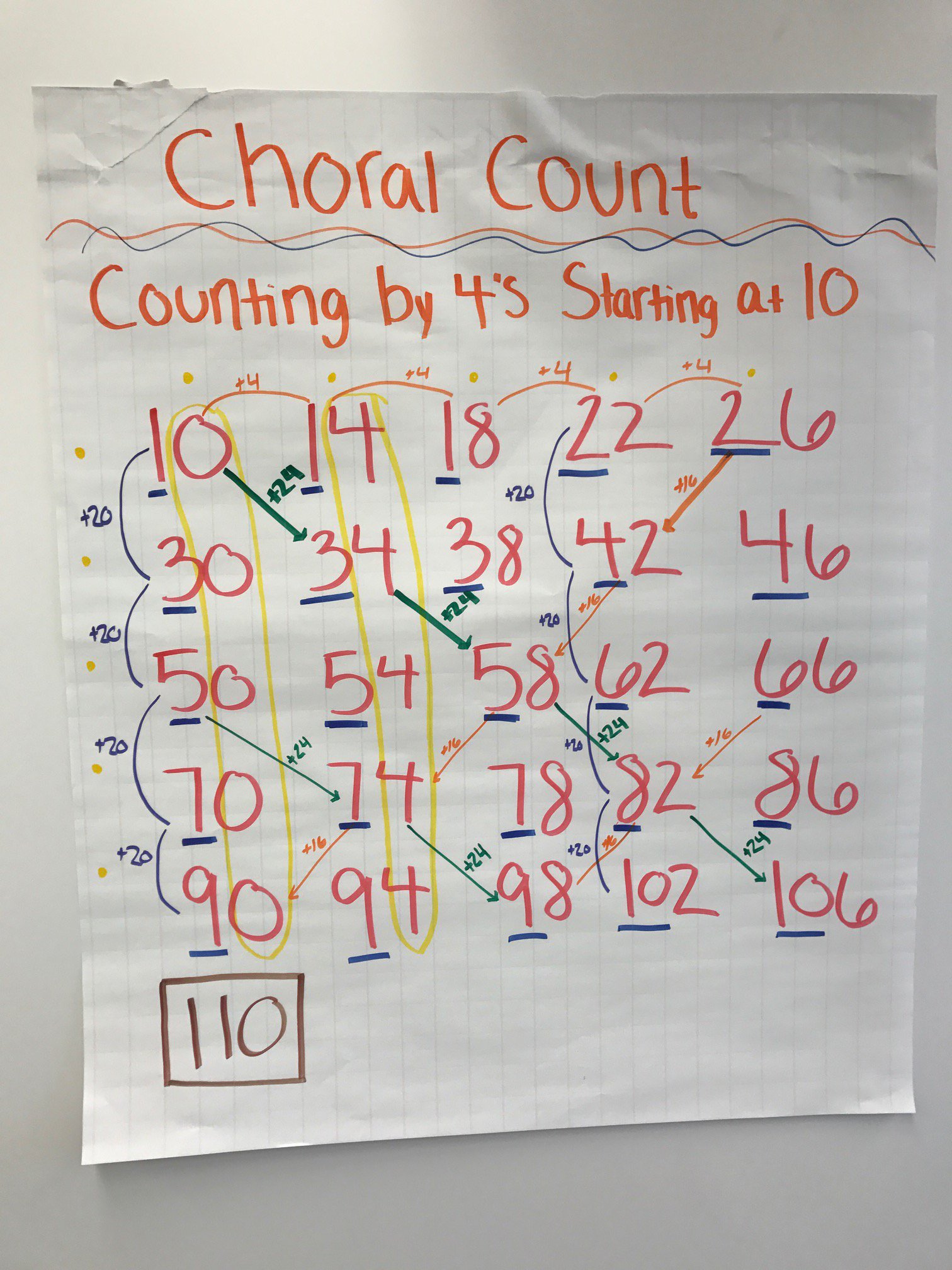

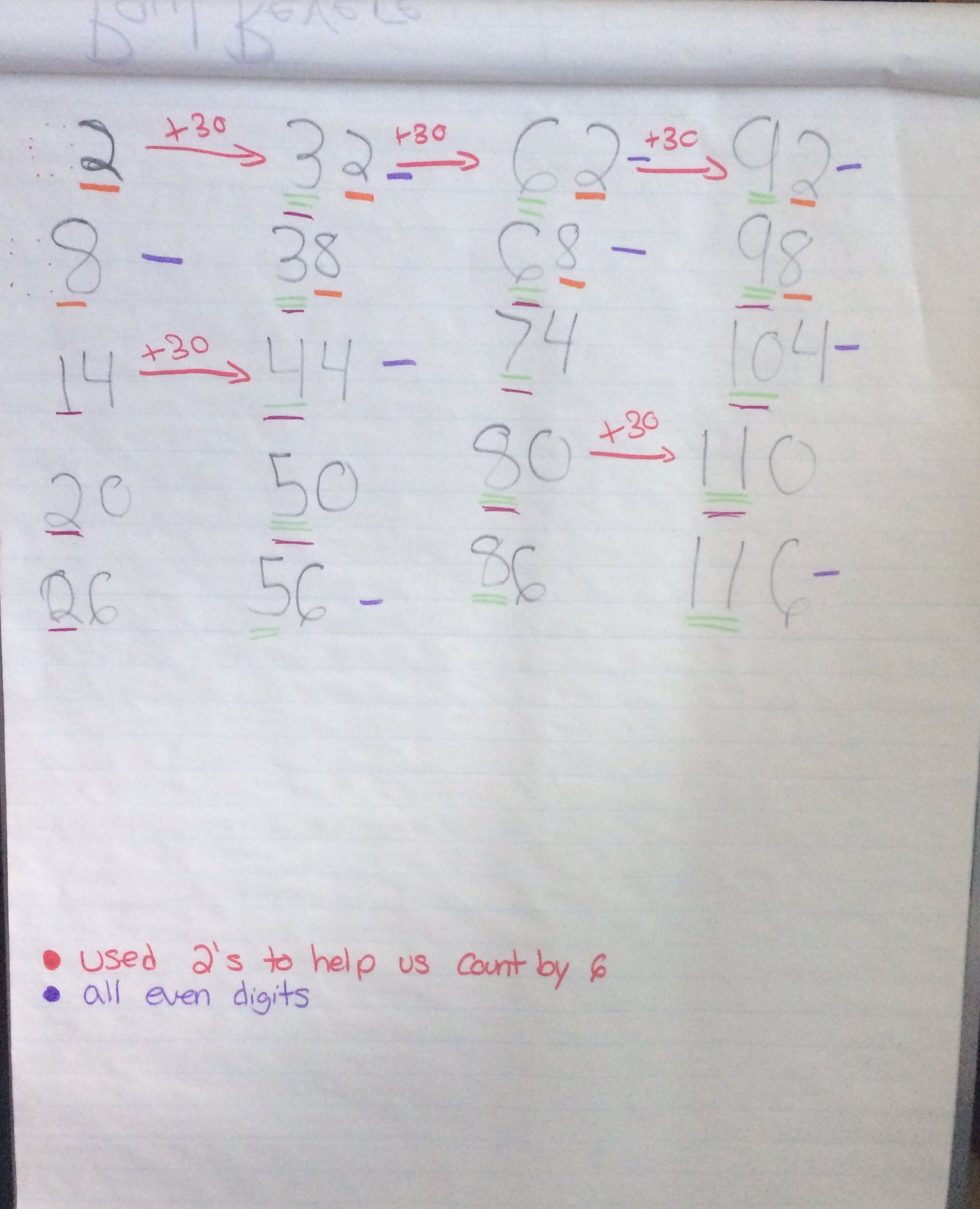

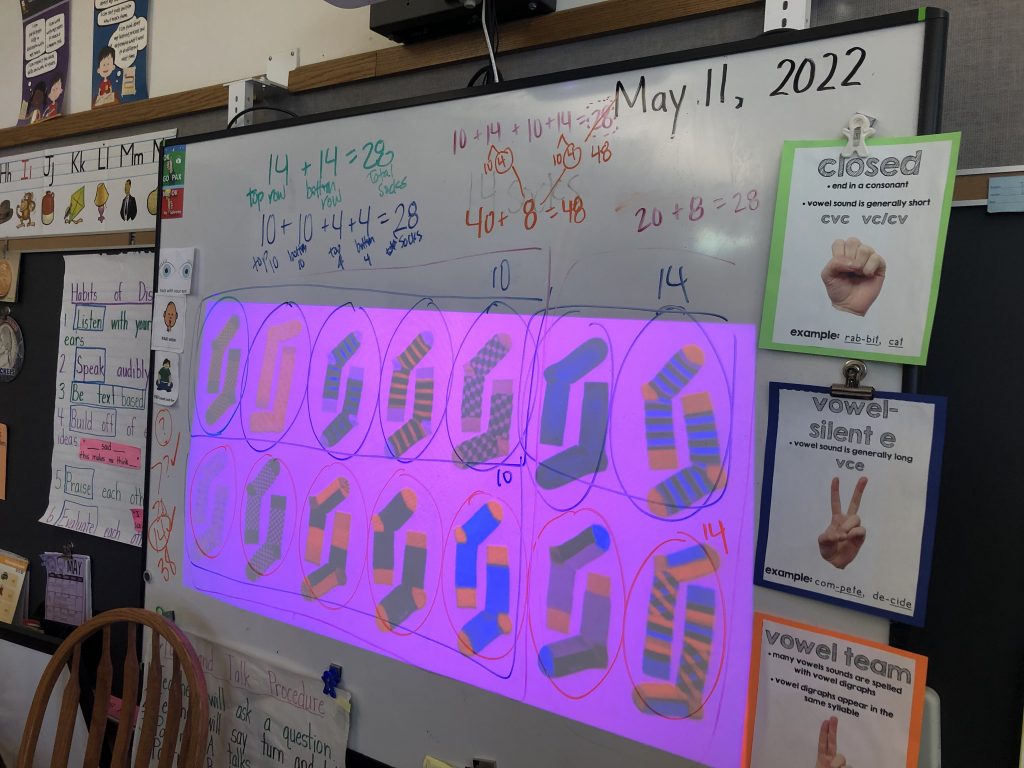

After about 15 minutes, Ben and the other two TPP teachers concluded their discussions, using number sentences to record their thinking. Ms. D. gave each TPP teacher a “Bunny Buck” (named after the school’s mascot) to give to students for sharing their thinking with voice, with generosity, and with explanations and reasoning. The students all gathered back on the rug at the front of the classroom for a short (10 minute) model lesson using imagery in a slightly different way. Unlike a quick image, in which students are asked to subitize and use visual patterns to group, mentally count, estimate, or multiply, a notice/wonder image asks students to think a bit more slowly about what they see, how they see it, and how they could use different units to describe the same image:

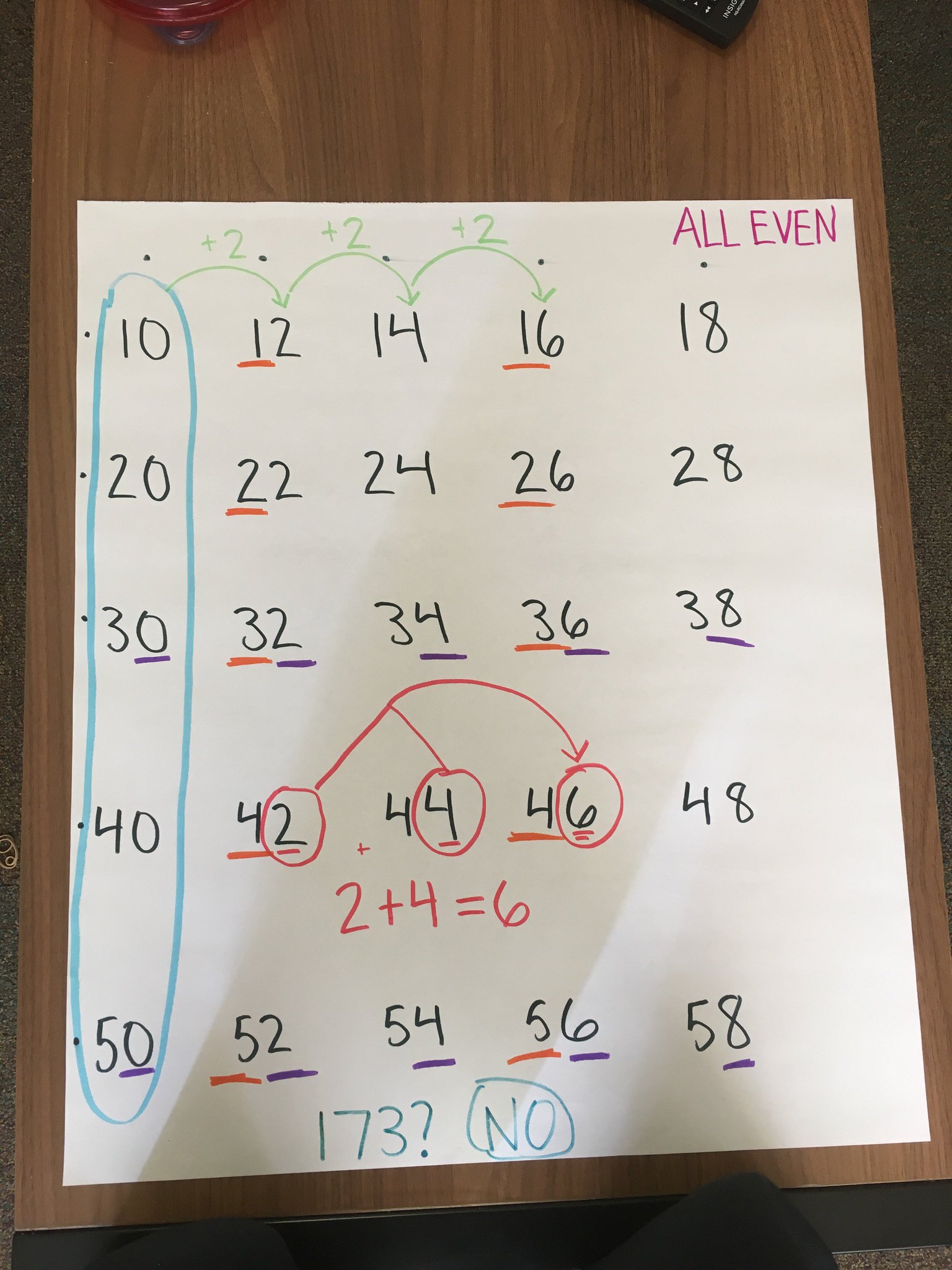

I had anticipated that this image might get students thinking about units of 1 or 2 – that is, socks or pairs of socks. In the end, we only ended up discussing individual socks – but the students arrived at the total number in several ways:

- Skip counting by 2s

- Adding each row as 14

- Subdividing each row into 10 and 4 more, and adding each row

- Grouping the 10s together into 20 and adding the 8 remaining socks

- One student shared the idea that we could find the total by adding 10+14+10+14.

This provided a great opportunity to talk about how teachers can handle ‘wrong answers’ – or in this case, unfinished strategies. The student was suggesting we add 10+14 because both numbers were written on the board – a vestige from when I had been ‘keeping track’ as we counted all together by 2s.

As a group, we discussed (in a turn and talk first, and as a whole group second) whether or not that total would really be 28 (we decided it was 48) and if there were really 48 socks or not (we counted by 1 to know for sure). I highlighted this as an opportunity for students to revise their thinking- and Ms. D reminded me to define ‘revise’ for the students.

I reflected in the moment, and now, whether I handled this student’s error appropriately, or whether I should have come back to her at the end to ask for her thoughts. My fear: what if she hasn’t revised her thinking and still insists that 10+14+10+14 would give us the total number of socks? Even after counting by 1s, some students have trouble deciding that their first thought isn’t the one to stick with. So I decided – perhaps wrongly – to assume (out loud) that she had revised her thinking, and that the issue was settled. I still feel uncertainty in this point, and know that if I were to do things again, I would go about this moment differently.

As students shared and I recorded, Ms. D. pointed out some of the things I was doing, labeling or marking them for the students to emphasize their importance as thinking strategies:

- Keeping track of what I had counted using circling/crossing out

- Grouping items into groups of 10 and labeling them

- Using a number sentence to capture my thinking

- Recording what the number sentences mean using labels

I (Charlotte) annotated these various ways of coming up with a total. By the end of the 10 minute discussion, our board looked like this:

I summarized this discussion by pointing out all the students had thought and shared to get to the final answer – and the variety of ways they had approached the problem. Ms. D summarized what she had seen – students sharing, being willing to explain their thinking, and growth in the TPP students, whom she had observed playing games with her students in the fall. You’ve all grown so much in your presence; you look like you’ve been doing this for 10 years now!

As we left the classroom and walked back to the TPP classroom, I overheard some of the students sharing their excitement.

It was fun – they didn’t use all the strategies we thought they might – I’m surprised how quickly I could learn their names – they’re so cute! – I wasn’t as nervous as I thought I’d be….

Back in the TPP classroom, we discussed (very briefly, with only 5 minutes until the bell would ring) the purpose of anticipating student thinking. This isn’t like mapping the directions from here to McDonalds, I told them. This is like searching for McDonalds on the map, and watching the map populate with all the different locations. We’re trying to build a map of the different student strategies that MIGHT emerge, and how we would handle them – not plan for a super specific sequence of strategies we must have shared. But by doing that planning, we’re more ready to hear, listen, and ask in response to what actually comes up.

All in all, we had a wonderful first MFE. I was reminded once again how fortunate we are to have such wonderful partners – the TPP Teacher, Ms. D., her collaborating teacher – and to have one another as we learn about teaching, by doing teaching – together.

-Charlotte