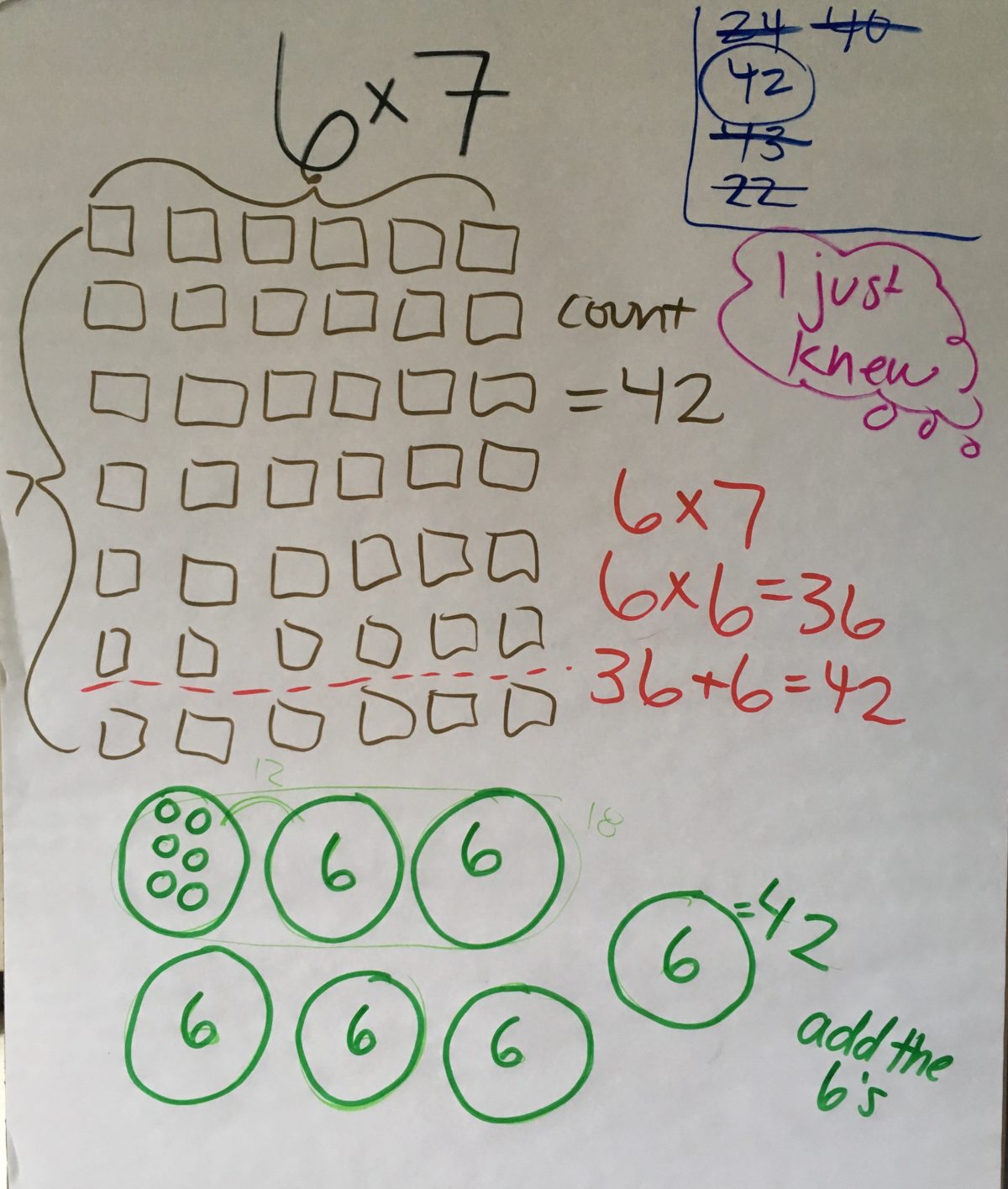

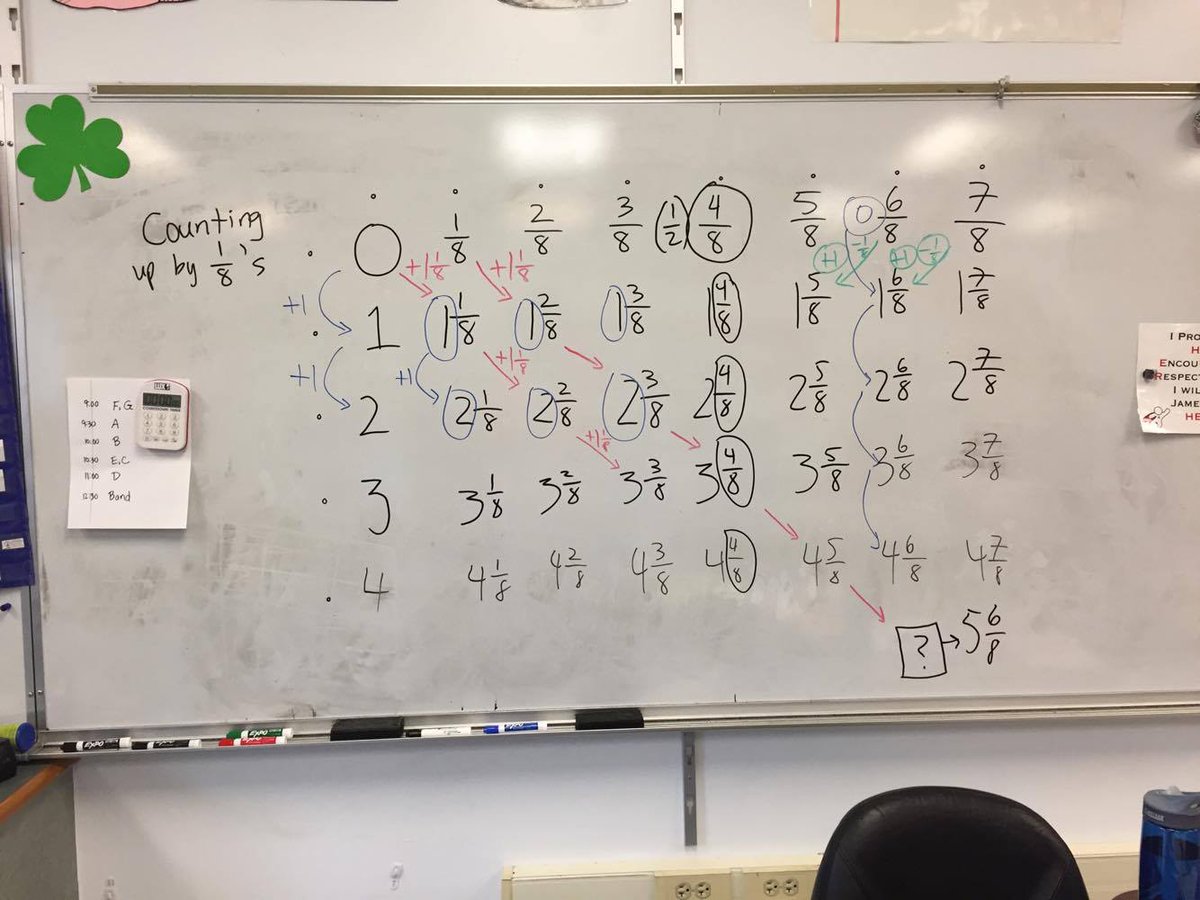

I think sometimes it’s easy to see Choral Counts for their glitter, and miss their substance. People quickly fall in love with them because they’re fun, engaging, interesting, and they get kids talking about math. And these are great reasons to love and choral counts! Beyond all this fun, though, choral counts (and the representations they produce) can support students to investigate really critical concepts – even in the older grades.

Yesterday I worked with some 5th grade teachers to plan some choral counts they can use in their current unit, which is all about fraction multiplication and division – specifically, division of whole numbers by fractions, and vice versa. Can choral counts support students in this unit? Absolutely.

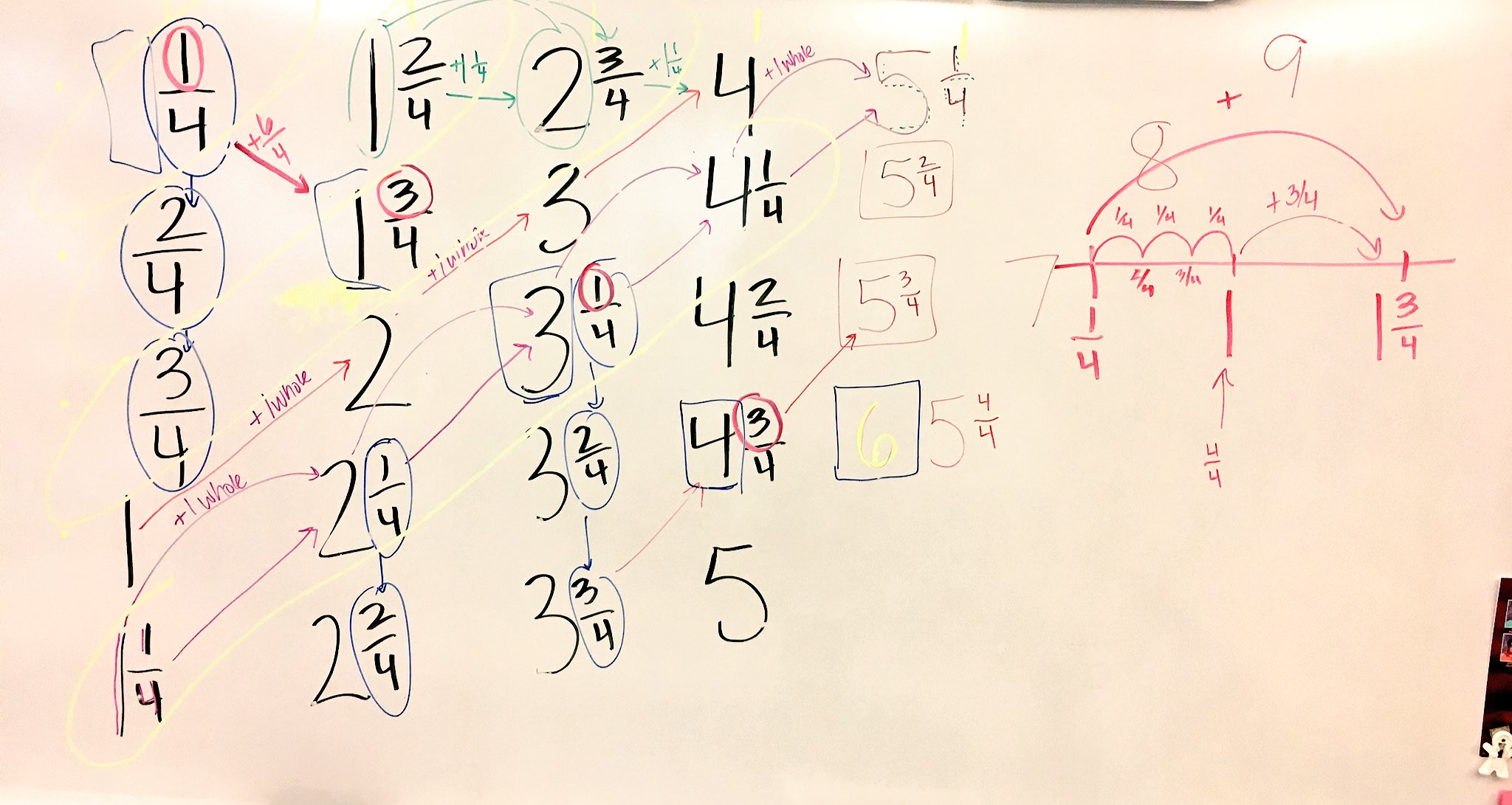

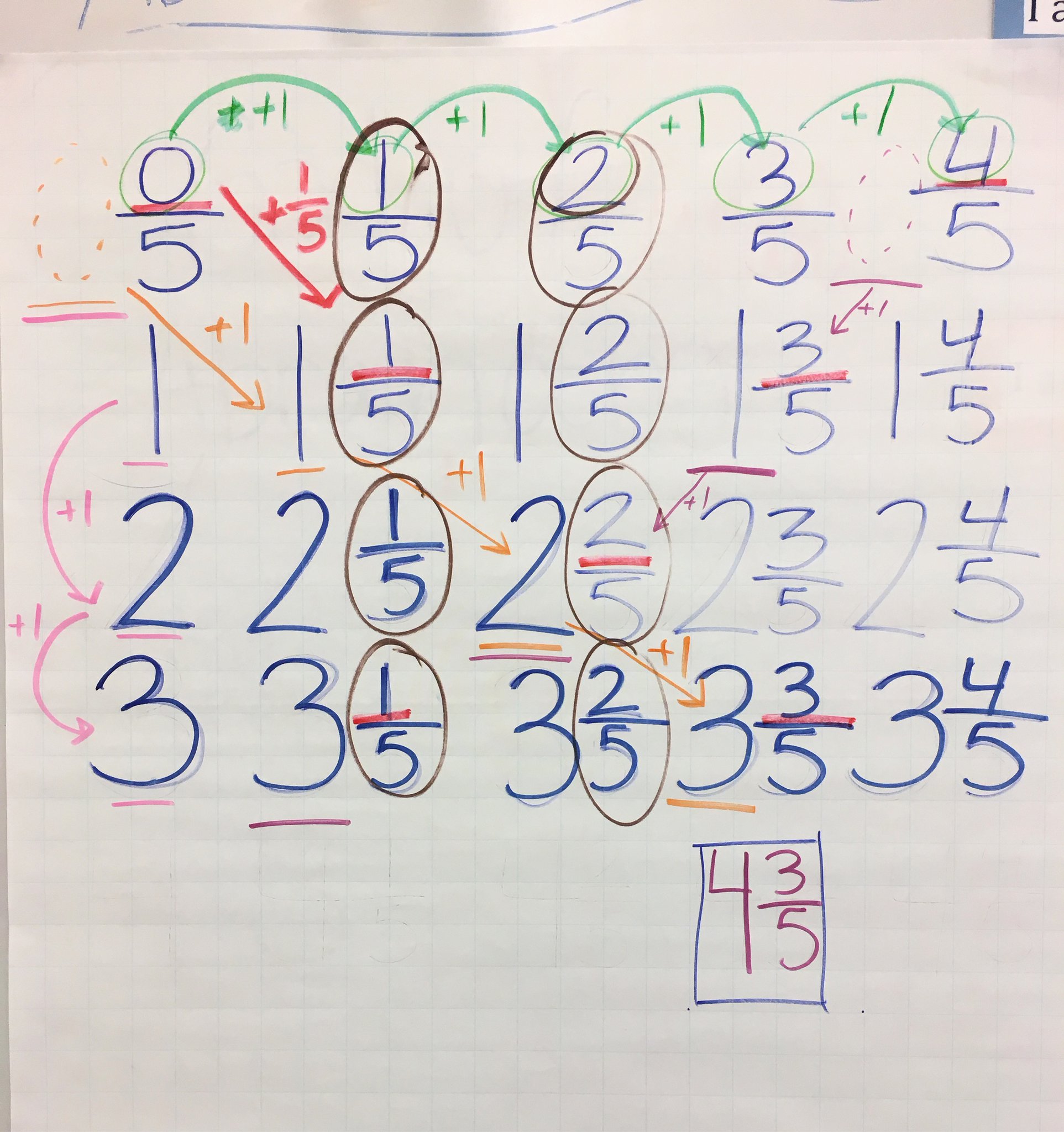

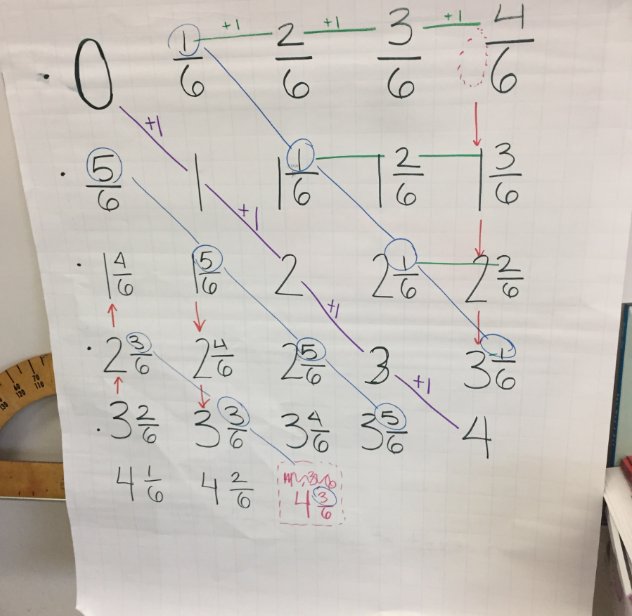

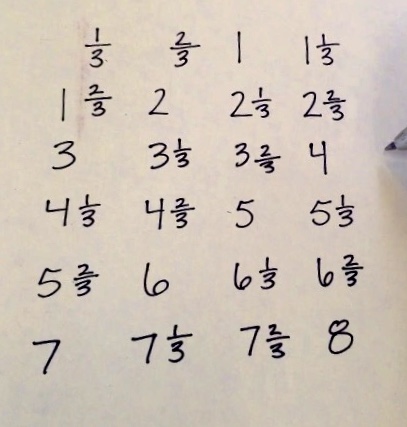

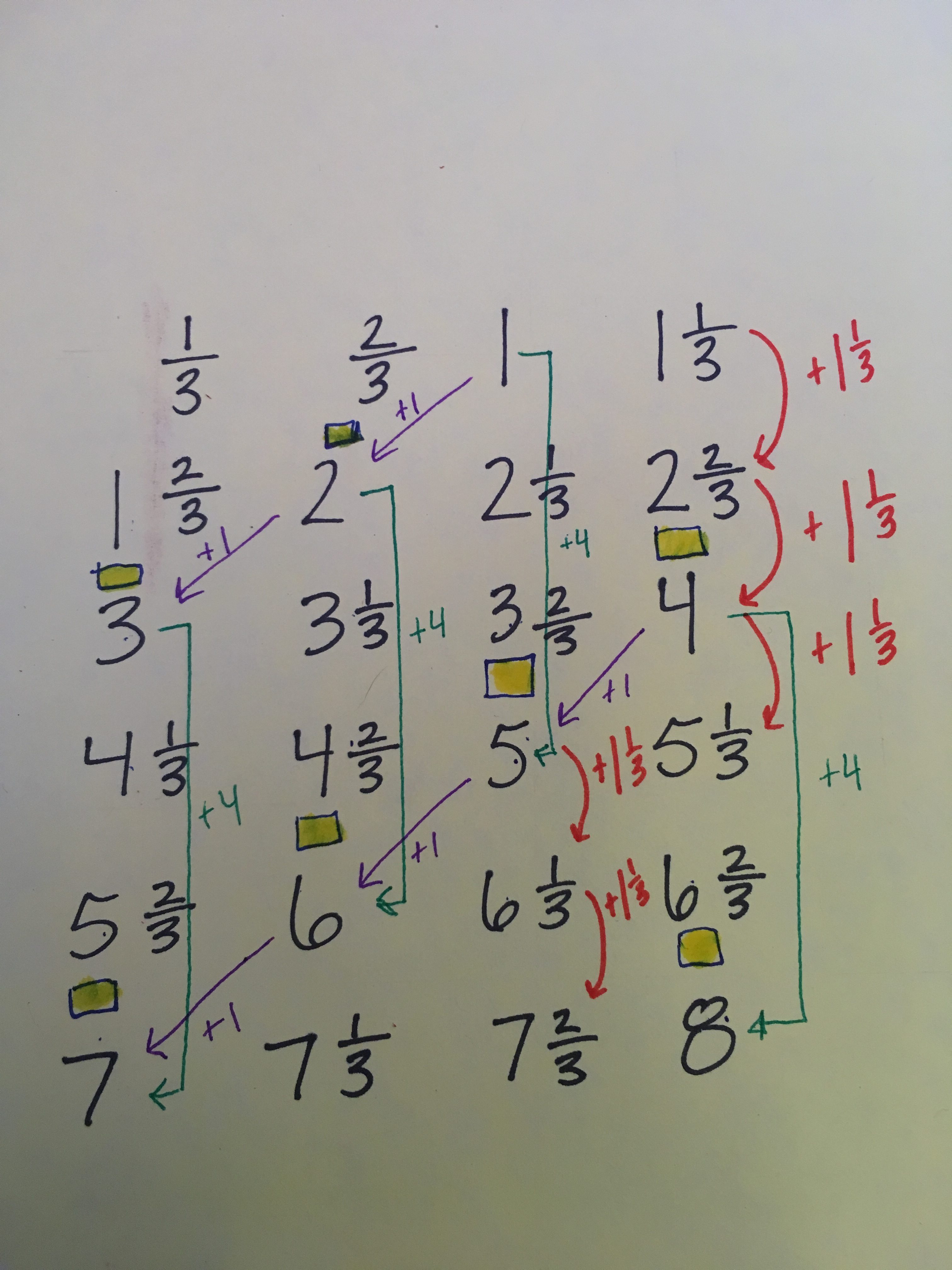

Check out this count we went through yesterday. We counted up by 1/3, starting at 1/3, using rows 4 across. I specifically chose to use rows of 4 in this count to make it “offset” in a way that would create some neat patterns. We found lots! What patterns do you see in this count?

Here are some we found:

- The down-left diagonals increase by 1.

- Three hops ‘down’ the column is an increase of 4 (this is especially apparent for the whole numbers, so that’s where I marked them.)

Each hop ‘down’ a column is an increase of 1 1/3.

- There are some “missing” whole numbers in each column: for instance, in the third column, there’s no 4. In the fourth column, there’s no 7.

By drawing a little box where all the missing numbers are, another interesting pattern emerges…

Ok ok ok, we could do this all day. But what about exploring fraction multiplication and division with this count?

Consider posing the problem 8 ÷ 1/3. How would you solve this problem mentally? How might 5th graders?

Now, try using the finished count to solve this problem.

.

.

.

(Think about it on your own before you scroll down.)

.

.

.

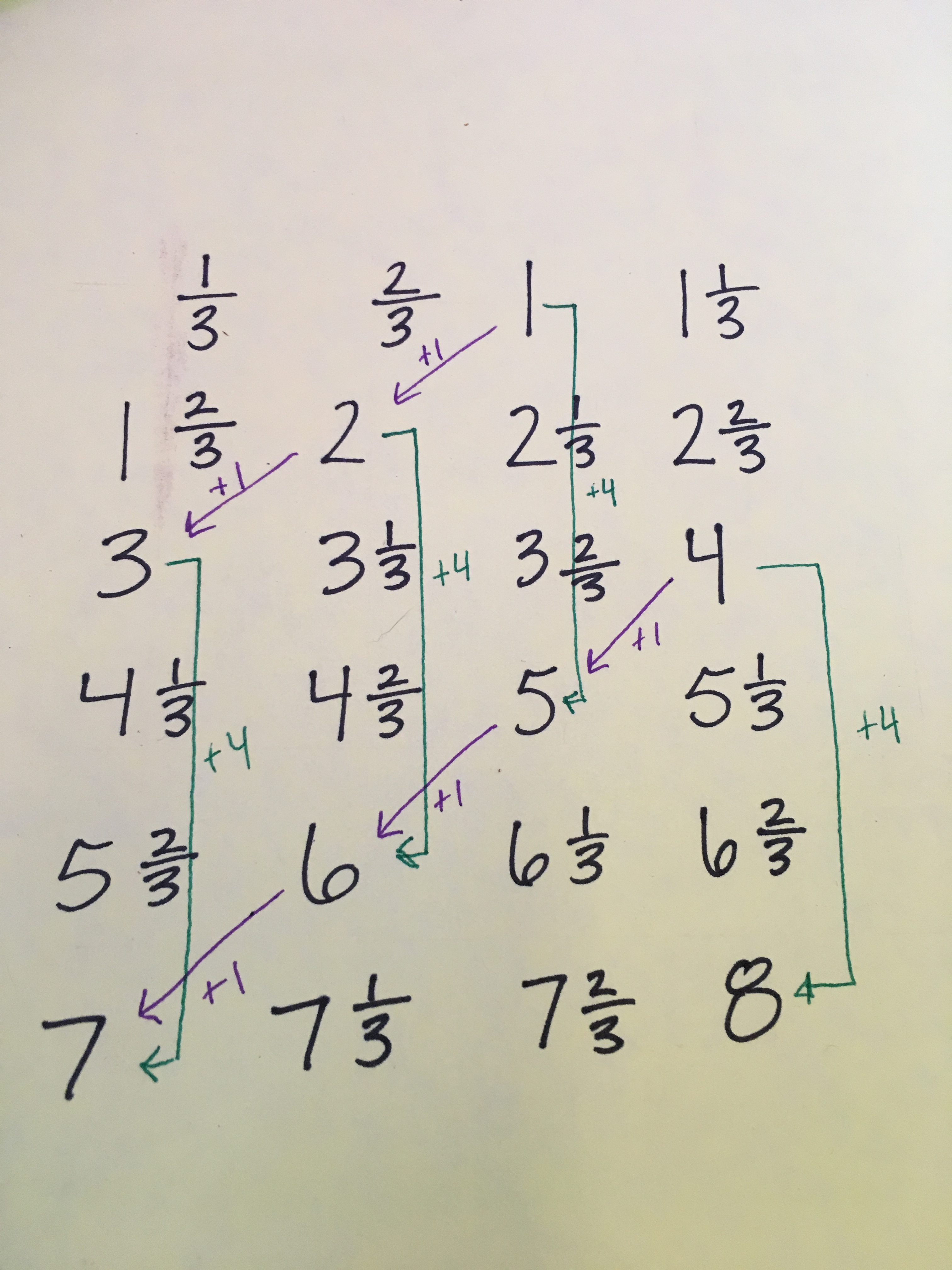

One way of thinking about 8 ÷ 1/3 is, “how many 1/3 counts does it take to get to 8?” So we can get the solution by counting our ‘hops’ in the count. Because we didn’t start at 0, we count the numbers, not the hops.

Something that struck us in our PD meeting yesterday was that this is a nice way for students to confront their (totally reasonable) preconception that dividing always ‘makes something smaller.’ But how can we hammer that home?

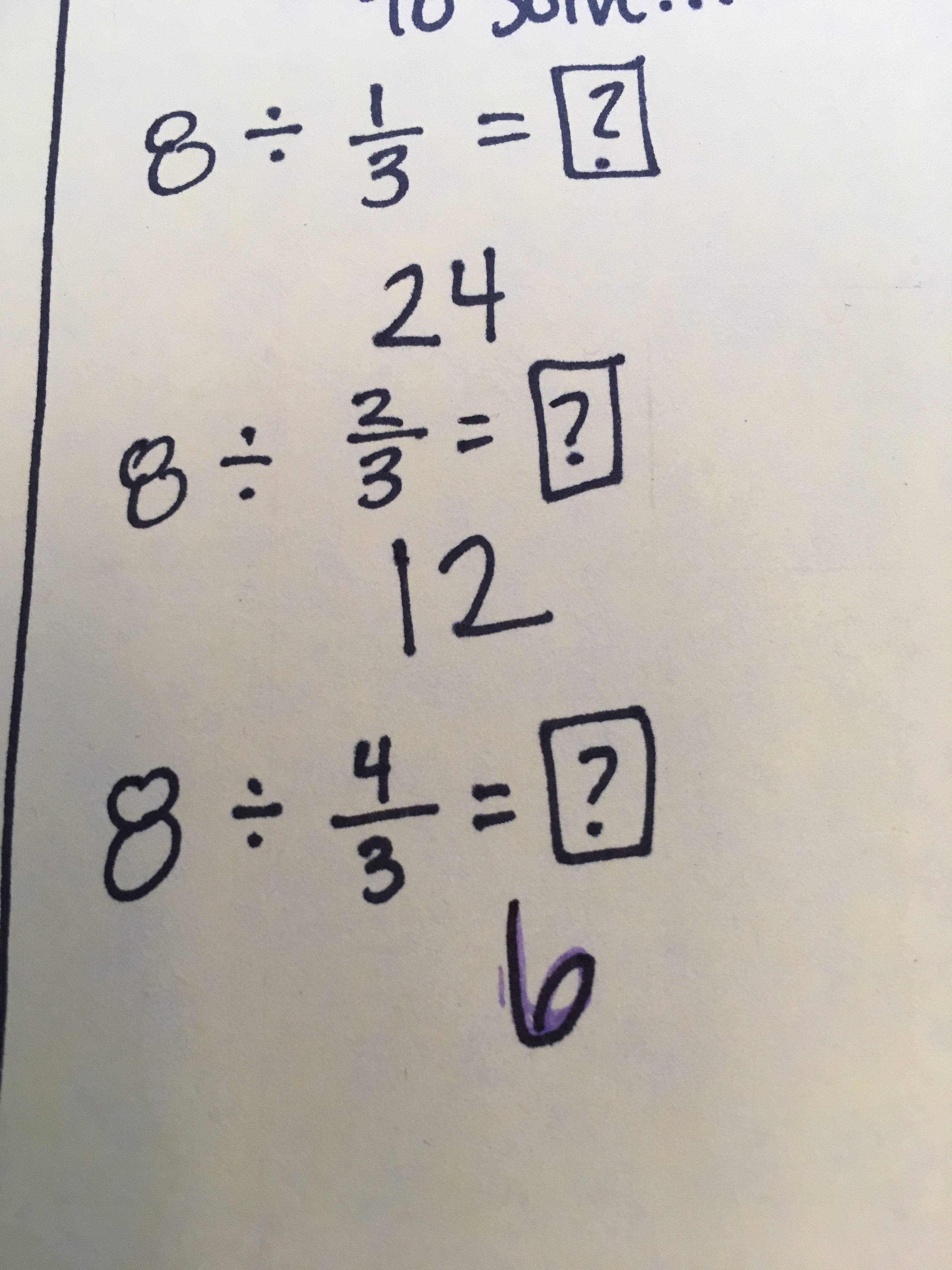

Consider adding more problems in a string – building larger divisors. How could you use the count to figure out

8 ÷ 2/3? Students first have to figure out what 2/3 looks like. Can you build 2/3 by grouping 1/3’s? Sure! So how would that help us solve the problem? Count the hops again – only this time, we’re counting 2 hops at a time.

Something we’d want students to really be firm on: 2/3 is larger than 1/3. It’s a larger divisor.

So, let’s check out one last problem: 8 ÷ 4/3. [First: we want students to make a mental note. 4/3 is larger than 1/3 and 2/3.] Woah woah woah – dividing by an improper fraction?? Why not? Again, students need to first figure out where 4/3 appears in the count: can you build 4/3 by grouping 1/3’s? sure! So using the same process we did above, we build a larger divisor and count those hops.

So now, let’s check out this string of problems and solutions that we’ve created. What might students notice? What big ideas might this string help them to make sense of? What questions might you as a teacher pose to students to get them thinking about those big ideas?

So, in sum, here are some big concepts you might explore in a choral count like this one:

- Fractions can be decomposed into unit fractions – and unit fractions can be grouped together into larger chunks – even into chunks larger than 1! This is actually a 4th grade standard, but it’s very likely that 5th grade students need more opportunities to see this concept in action.

- Dividing something relatively big by something smaller means fitting small things into something big. So we shouldn’t automatically expect the quotient to be a smaller number than the dividend. This is essentially applying a 3rd-grade understanding of the meaning of division to fractions – and thereby arriving at a key 5th grade standard.

- The larger the divisor is, the bigger the thing is we’re trying to ‘fit’ into the dividend. A related idea is that the closer the divisor is to 1, the closer the quotient will be to the dividend.

Have you used choral counts in your classroom to explore and model similar concepts? Tell me about it in the comments – I’d love to hear!